|

| 7/11/14 - Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City - Jaguar Warrior Head |

|

| 7/11/14 - Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City - Eagle Warrior Head |

|

| 7/11/14 - Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City - Tlaloc Door Ornamentation |

Construction on this building originally began in 1904 but wasn’t inaugerated until 1934. At the beginning, the structure was intended to be finished by 1910 as part of the 100 year anniversary of Independence. However, construction conflicts arose as did the Revolution and put a halt on the project. However, given the timing, this building offers a look at two different periods in Mexican history: the end of the regime of Porfirio Diaz with his nod to European style and the Revolutionary period with the final work housing murals by of the most renowned Mexican muralists of the time (Mexican Tourist Board 2012). For the artists of the Revolution, it was “The return to native values, spiritual and artistic, which is a simplified description of modern Mexican art, in the case of the founders of this new tradition often occurred by way of modern European art” (Brenner 2002).

|

| 7/13/14 - Instituto Cultural Oaxaca, Oaxaca, OAX - Protest Poster with Speech Bubbles and Footprints |

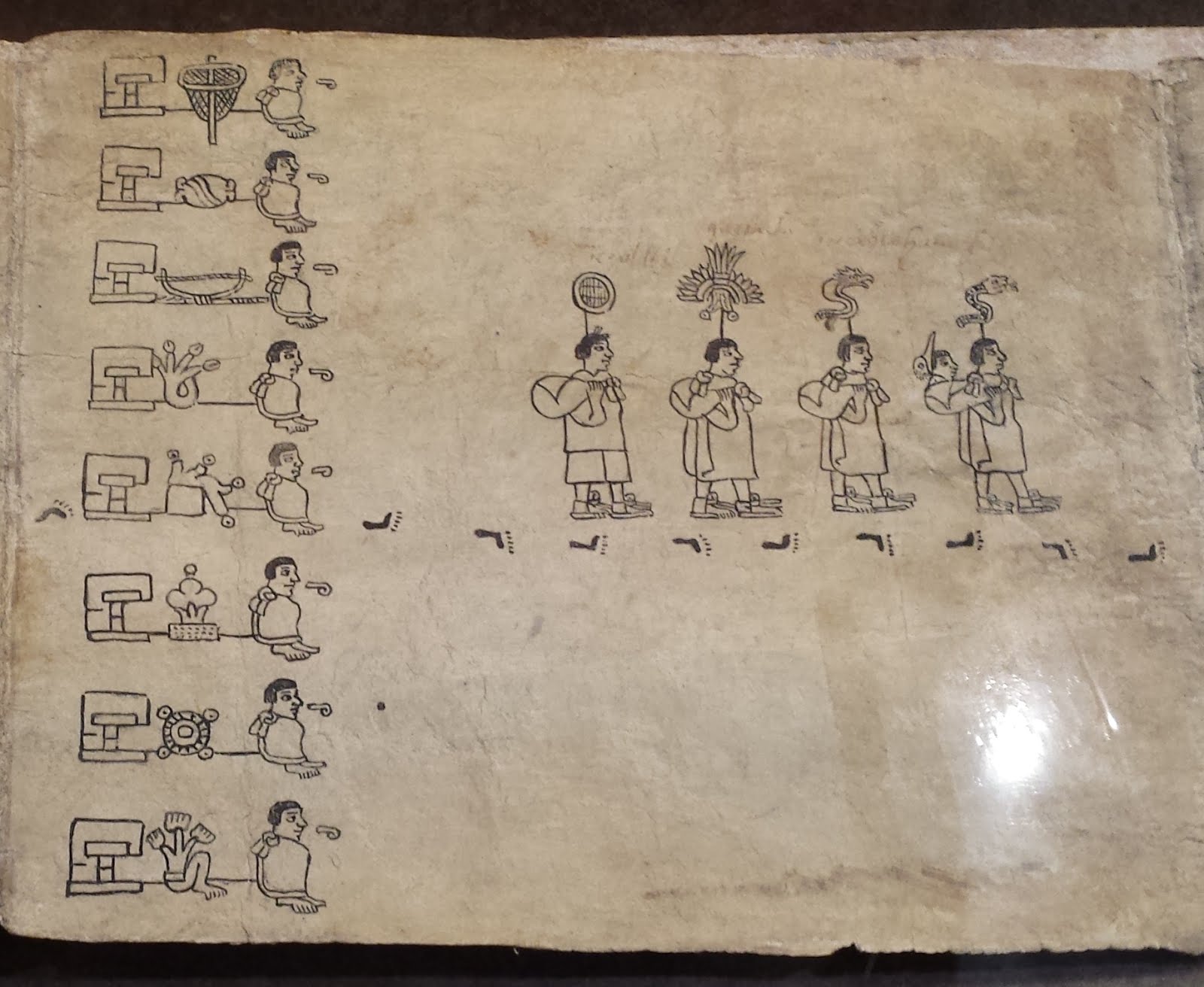

We were no strangers to protests while in Mexico. This image uses footprints as an indicator for movement or pathway. It also uses speech bubbles, which are commonly seen in codices indicating, communication. Examples of these forms of iconography are present in the mythology of Aztec origin codex:

|

| 8/8/14 - Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City - Excerpt from Aztec Origin Codex |

|

| 7/13/14 - Porfirio Diaz (Road? Avenue?), Oaxaca, OAX - Bridge Ornamentation Featuring (likely) Cosijo |

|

| 7/13/14 - Porfirio Diaz (Road? Avenue?), Oaxaca, OAX - Bench with Unknown Figures |

Zapotecas make up the largest group of indigenous peoples in Oaxaca and as such, it was common for us to see descriptions at museums and archaeological sites offered in Spanish, English, and Zapotec. It was also common for deities and artistic styles attributed to the Zapotecas to appear throughout the city. Though I cannot be certain about the deity on the bench, the style is reminiscent of the geometric patterns commonly found in Mitla. The image Cosijo on the bridge is nearly identical to several ceramic sculptures we viewed at the Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca.

|

| 7/15/14 - José López Alavez (Road? Avenue?), Oaxaca, OAX - Mural by artists Búho Villamil and Lucia Rivera G. |

I looked for an explanation for this particular image and was unsuccessful. The artists who created this vivid mural have created many other beautiful pieces and I recommend looking them up on Facebook. Besides the image, one of the most striking features about this mural that I noticed is the color pallette. It seems to me that the artists chose to stick with traditional colors and hues that were often used on not only the frescos, but the exteriors of buildings. These ranges of colors were seen on ceramic sculptures in the Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, on the frescos in Teotihuacan, and on the recreated exterior of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl featured in the Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Mexico City.

|

| 7/16/14 - José López Alavez (Road? Avenue?), Oaxaca, OAX - Mural Image 1: Note the Speech Bubble in Yellow to the Right of the Large Window |

|

| 7/16/14 - José López Alavez (Road? Avenue?), Oaxaca, OAX - Mural Image 2. |

I originally had seven pictures of this mural because it was covering a wall that spanned nearly half of a block. Beyond the one speech bubble visible in Image 1, there are also geometric patterns similar to those seen at Mitla. The images used in this mural vary, though I commonly saw small sections which resembled compasses. For several known ancient Mesoamerican cultures, the cardinal directions were important to elements in religion and spirituality. To further reinforce the common use of indigenous elements or imagery, take a moment to use Google Street View for this section of wall to see how it was previously adorned: https://www.google.com/maps/@17.076205,-96.722913,3a,75y,130.58h,75.75t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1s8prNkJ4q2I4AHFbJIbLjzQ!2e0

|

7/26/14 - Carretera Internacional, Oaxaca, OAX - Monument to Benito Juarez (the glyph likely represents "Oaxaca")

This is one of many monuments/memorials for Benito Juarez. Juarez, known also for his Zapotec heritage, has become a figure of mythical proportions and is widely celebrated throughout the world. This monument celebrates his life and accomplishments. It includes a glyph that to the best of my searching appears to be the symbol for “Oaxaca" featured in the bottom left-center of the mosaic.

|

|

| 8/7/14 - Filomeno Mata, Garden of the Triple Alliance, Historic District Mexico City - Bronze Castings of Two of the Three Leaders of the Aztec Triple Alliance: Izcoatl and Nezahualcoyotl |

Mexico City was once the seat of the Aztec rule and though very colonialized, there are references to the former occupants. In the image above are two of the three leaders responsible for the Triple Alliance: Nezahualcoytl of Texcoco, Izcoatl of Tenochtitlan, and Totoquihuatzin of Tlacopan. These three worked to create a unified Mexica rule over the surrounding cities.

The image below adorns the Palacio Nacional and presents the State symbol of Mexico situated between an Eagle Warrior and a Spanish Conquistador. This building was established at the time of conquest and was specifically built on the ruins of the palace of Mocteczuma Xocoyotzin on orders by Hernan Cortes.

|

| 8/7/14 - Palacio Nacional, Historic District, Mexico City - The Eagle in the Emblem Faces an Aztec Eagle Warrior |

|

| 8/3/14 - Plaza Santo Domino de Guzman, Oaxaca, OAX - Image 1: The Base is Reminiscent of Carved Tzompantli Skulls |

|

| 8/3/14 - Plaza Santo Domingo de Guzman, Oaxaca, OAX - Image 2: The Base is Reminiscent of Carved Tzompantli Skulls |

These sculptures were another interesting addition to the Plaza de Santo Domingo de Guzman in Oaxaca. From a distance, the engravings on the animals look glyph-like, but they are not. The bases of each animal (not specifically indigenous to the country) are covered with skulls. I was not able to locate further information regarding the artist or their intent behind each engraving, however, the style of the skulls resemble those seen at Templo Mayor in Mexico City:

|

| 8/8/14 - Tenochtitlan, Mexico City - Tzompantli |

|

8/7/14 - Interior Palacio Nacional, Historic District, Mexico City - Section of Diego Rivera Mural Highlighting Pre-Conquest Indigenous Groups

Diego Rivera’s mural inside the Palacio Nacional accounts the history of the Mexican people from the time of Quetzalcoatl to 1930. Impressively, Rivera does not hold back in painting painful, tragic, and even controversial events. He illustrates the abuses that were heaped upon the Aztecs by the conquerors and finishes this mural by illustrating the abuses heaped upon the laborers by elite.

--------------

|

One of the most refreshing aspects of my Mexico experience were the thriving indigenous cultures. These cultures survive for a number of reasons. Firstly, there are 15 recognized languages of Mexico: a number that does not reflect the scores of dialects within those languages. Secondly, it is estimated that the Spanish were responsible for killing approximately 95% of the indigenous population. Many people of Mexico are Mestizo, a mix of indigenous and Spanish descent, however some groups have maintained purely indigenous bloodlines for hundreds of years. For these people, culture and heritage is maintained through preservation of language, dance, clothing, and often art.

Sandra Rozental writes in her piece, “Stone Replicas: The Iteration and Itinerancy of Mexican Patrimonio” about how cultural identity also exists through location. In Coatlinchan, for example, the conquered people had a relationship to a monolith of Tlaloc and their imposed patron saint, San Miguel. Each deified figure had significance. The relationship to these figures was more than pride, it was a sense of cultural ownership. When the State enacted patrimonio nacional, the ownership of history became the right of the masses and not of the few, per the demands. Patrimonio was created for numerous reasons, including to preserve the remaining history and as a means to prevent artifacts from leaving the country. However, this also meant that the government could take possession of any and all artifacts and had complete control over their use and placement. This created a deficit for the people of Coatlinchan when the State removed their Tlaloc and installed it in the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, effectively stealing a piece of history from the community that had existed around it for hundreds of years or more. “...19th-century scholars found this Coatlinchan monolith and other pre-Hispanic artifacts to be tangible traces of an ancient civilization, and an alternative, non-Spanish and non-Christian patrimonial anchor for the new geneaology of the nation” (Rozental 2014).

A supplement to patrimonio nacional is the right of the State to produce many recreations of the “reclaimed” artifacts.Though the use of recreations can have positive attributes, the abundance of recreations for particular artifacts falls into commercialization. Rozental writes, “...I analyze the multiplication of the monolith as an index of Mexican modernity in the shape of miniatures and souvenirs that materialize the State’s ideological project of mestizaje” (2014). People who have histories and mythologies invested in these original artifacts are less than enthusiastic about the reproductions. For the Tlacauches and the people of the Coatlinchan, they eventually created a life-size replica and performed a ceremony during which they imbued the statue with the powers of the original.

Yes, the State uses patrimonio nacional for the purpose of secured preservation of artifacts and national heritage. Most of the nation is mestizo, making them of mixed Indigenous and Spanish origin and there is a strong sense of nationality present. However, according to Octavio Paz in The Labyrinth of Solitude, that sense of pride was not immediate: “The Mexican and his Mexicanism must be defined as separation and negation. And, at the same time, as a search, a desire to transcend this state of exile” (1985). For Paz, exile was a sense of not belonging to either group, but rather a new group of Mexicans who were orphaned through the Conquest and continue to search for their place. Independence from Spain asserted that Mexico was something different and “After a hundred years of struggle the people found themselves more alone than ever, with their religious life impoverished and their popular culture debased. We had lost our historical orientation” (Paz 1985). The Revolution was the next step to try and reunite orphaned Mexicans with the Mexico they had fought for and inherited.

Anita Brenner shares in Idols Behind Altars: Modern Mexican Art and Its Cultural Roots:

“In the span of one generation Mexico has come to herself. Her first and definitive gesture is artistic. While the government shifts and guerillas still battle for Cristo Rey and other interests, the builders, necessary as the destroyers, refound the nation. It is a nation which establishes a school for sculpture before thinking of a Juvenile Court, and which paints the walls of its building much sooner than it organizes a Federal Bank. Sanitation, jobs, and reliably workable laws are attended to literally as a by-product of art: for the revolution is a change of regime, because of a change in artistic style, or if one wishes a more usual description, of spirit.”

These images are mixes of the old and the new: generations of Mexicans who are still working to find themselves in the past and present.

------------------------------

Bibliography:

Brenner, Anita. Idols Behind Altars: Modern Mexican Art and Its Cultural Roots. New York: Dover,

2002. Print.

Paz, Octavio. The Labyrinth of Solitude: and The Other Mexico Return to the Labyrinth of Solitude

Mexico and the United States The Philanthropic Ogre. New York: Grove Press, 1985. Print.

Rozental, Sandra. "Stone Replicas: The Iteration and Itinerancy of Mexican Patrimonio." The

Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology. Vol. 19. No. 2 (2014): pp. 331-356.

Web. 14 Aug. 2014.

"Aztec: Fierce Wanderers." Nature on PBS. Thirteen Productions, LLC., 2014. Web. 15 Aug. 2014.

"Bellas Artes Palace." Visit Mexico. Mexico Tourism Board, 2012. Web. 15 Aug. 2014.

"Murals." Palacio Nacional Mexico. Secretaria de Hacienda y Credito Publico, n.d. Web.15 Aug.

2014.